A few of my readers use this blog to snap out of their funk. I used Ray Williams’ Monday Morning Memo the same way… I also use Rob Brezsny’s weekly horoscope the same way. My Sunday call with a friend mostly works out that way too…

A few of my readers use this blog to snap out of their funk. I used Ray Williams’ Monday Morning Memo the same way… I also use Rob Brezsny’s weekly horoscope the same way. My Sunday call with a friend mostly works out that way too…

We all need something that returns us to sanity, to coherence, and to get aware, again, what is important in life.

This article was especially potent for me this morning.

My Sadly Comical Midlife Crisis

I got some great news last week. A friend who read my Musings of an Old Ad Writer said to me, “You’re not old, you’re middle aged.”

Woo-hoo! If he’s right, I’m going to live to be 114.

During the years that I was, in fact, middle aged, I was too busy to have a midlife crisis.

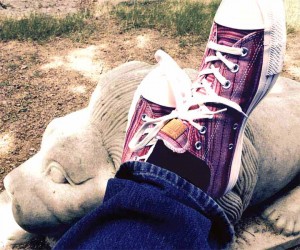

So I decided to have one now.A midlife crisis, as I understand it, is a ridiculous and ill-advised grab at the fleeting shadow of one’s former years. So I chose to reclaim my lost youth by wearing a distinctive brand of canvas shoes that defined me when I was a kid. Zappos was happy to send 5 pairs of this wildly inappropriate footwear and I began wearing them everywhere I went.

No one seemed to notice. Then I learned that my “new look” is the standard uniform of silicon valley CEOs.

Crap. I can’t even conjure up a credible mid-life crisis. (I’m continuing to wear the shoes though, because they’re even more comfortable than I remembered.)

The good thing about forgetting to have a midlife crisis is that you avoid a lot of pain.

When I was one year old, John Steinbeck wrote a letter to his agent, Elizabeth Otis, in which he expressed regret over what his midlife crisis had cost him.

I’m going to do what people call rest for a while. I don’t quite know what that means – probably reorganize. I don’t know what work is entailed, writing work, I mean, but I do know I have to slough off nearly fifteen years and go back and start again at the split path where I went wrong because it was easier. True things gradually disappeared and shiny easy things took their place.”

– John Steinbeck, Dec. 30, (the day before New Year’s Eve,) 1959From Steinbeck: A Life in Letters

John Steinbeck was neither the first nor the last to feel those feelings and think those thoughts.Humanity has long been distracted by “shiny easy things” but rarely does anyone publicly admit they made a dumb move “at the split path where I went wrong because it was easier.” Keep in mind that Steinbeck never meant for his letter to be published. He was writing only to his agent, Elizabeth Otis.

Oscar Wilde wrote a similar, private letter 118 years ago. Oscar was an Irishman living in London during the years leading up to the Spanish-American War. He died 2 years before John Steinbeck was born.

In his youth, Oscar was a sparkling novelist and playwright, a bon vivant and a wastrel with a dazzling wit. At the height of his fame, Oscar was imprisoned for being gay. After serving 2 years, he was released in May, 1897.

Three weeks later, he wrote a letter to his friend, William Rothenstein.

…I know, dear Will, you will be pleased to know that I have not come out of prison an embittered or disappointed man. On the contrary. In many ways I have gained much. I am not really ashamed of having been in prison: I often was in more shameful places: but I am really ashamed of having led a life unworthy of an artist. I don’t say that Messalina is a better companion than Sporus,* or that the one is all right and the other all wrong: I know simply that a life of definite and studied materialism, and philosophy of appetite and cynicism, and a cult of sensual and senseless ease, are bad things for an artist: they narrow the imagination, and dull the more delicate sensibilities. I was all wrong, my dear boy, in my life. I was not getting the best out of me. Now, I think with good health, and the friendship of a few good, simple nice fellows like yourself, and a quiet mode of living, with isolation for thought, and freedom from the endless hunger for pleasures that wreck the body and imprison the soul, – well, I think I may do things yet, that you all may like. Of course I have lost much, but still, my dear Will, when I reckon up all that is left to me, the sun and the sea of this beautiful world; its dawns dim with gold and its nights hung with silver; many books, and all flowers, and a few good friends; and a brain and a body to which health and power are not denied – really I am rich when I count up what I still have: and as for money, my money did me horrible harm. It wrecked me. I hope just to have enough to enable me to live simply and write well.”

Oscar Wilde died in Paris in November, 1900, at the age of 45.

John Steinbeck recovered from his midlife crisis and so did sparkling Oscar. Both of them returned to their work as writers with a heightened appreciation for the simple pleasure they took in the daily labor of it.

To what wheel do you put your shoulder each day? On what do you labor?

John Steinbeck and Oscar Wilde could have saved themselves a lot of pain if they had read the open confessions of Solomon who describes in his Ecclesiastes what may have been history’s most opulent and elaborate midlife crisis.

In chapter one, Solomon says,

I applied my mind to study and to explore by wisdom all that is done under the heavens.”

But he finds this grand quest for knowledge to be pointless, hollow and empty. So he changes direction in the second chapter,I said to myself, ‘Come now, I will test you with pleasure to find out what is good.'”

After several pages chronicling how he flung himself headlong into this and that, Solomon concludes that laughter and drunkenness and sex and accomplishment and great wealth are all equally empty:

I denied myself nothing my eyes desired;

I refused my heart no pleasure.

My heart took delight in all my labor,

and this was the reward for all my toil.

Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done

and what I had toiled to achieve,

everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind;

nothing was gained under the sun.

So did Solomon ever find an answer?Interestingly, his best advice is found at the end of chapter two:

A person can do nothing better than to eat and drink and find satisfaction in their work. This too, I see, is from the hand of God.”

Solomon’s point was this: “Choose to enjoy your work. Because when you do, every day is a good day.”

So enjoy the day! This day.

Yes, this one.

Solomon had no better advice.

And neither do I.Roy H. Williams

It is so darn easy to forget that choosing the eternal is the way of the smart ones…